- SERVICES

- THREATS

- Sector-based threat landscape

- Agriculture

- Energy

- Maritime

- Manufacturing

- Technology

- Logistics

- Governments

- Country threat profiles

- Russian Federation

- China

- Iran

- North Korea

- United States

- Israel

- Threat actor profiles

- Fancy Bear/APT28

- Cozy Bear/APT29

- OilRig/APT34

- Charming Kitten/APT35

- Lazarus/APT38

- Double Dragon/APT4

- Sandworm

- Seaturtle

- Silent Librarian

- RESOURCES

- ABOUT US

- CONTACT

iSoon leak sheds light on China’s use of extensive hacker-for-hire ecosystem

Last month, a treasure trove of data related to Chinese hacking contractor iSoon (also known as An Xun) was published to GitHub by a suspected whistleblower. The leaked files, which include marketing materials, spreadsheets and chat logs, provide rare insight into China’s extensive hacker-for-hire ecosystem and challenge many of the assumptions held by the security community up to this point.

iSoon operates within a tangled web of Chinese threat actors including state sponsored APTs, contract organizations and hacktivist groups working to advance China’s strategic interests through cyberspace. In this blog post, we delve into the leaked documents and examine what they can tell us about China’s contract hackers, as well as the broader ecosystem that enables outsourcing of cyber operations to the private sector.

Summary of the iSoon leak

On February 16, more than 500 files related to Shanghai Anxun Information Company (otherwise known as iSoon) were leaked online by a suspected whistleblower. iSoon is a contract organization which provides hacking services, technology and tools to public sector organizations in China. The company maintains its headquarters in Shanghai, with subsidiaries and offices in Beijing, Sichuan, Jiangsu and Zhejiang.[1] Its largest client is the Ministry of Public Security, which maintains responsibility for domestic security and law enforcement in China. It appears iSoon is primarily utilized for mass data harvesting and surveillance of Chinese dissidents both at home and abroad.[2]

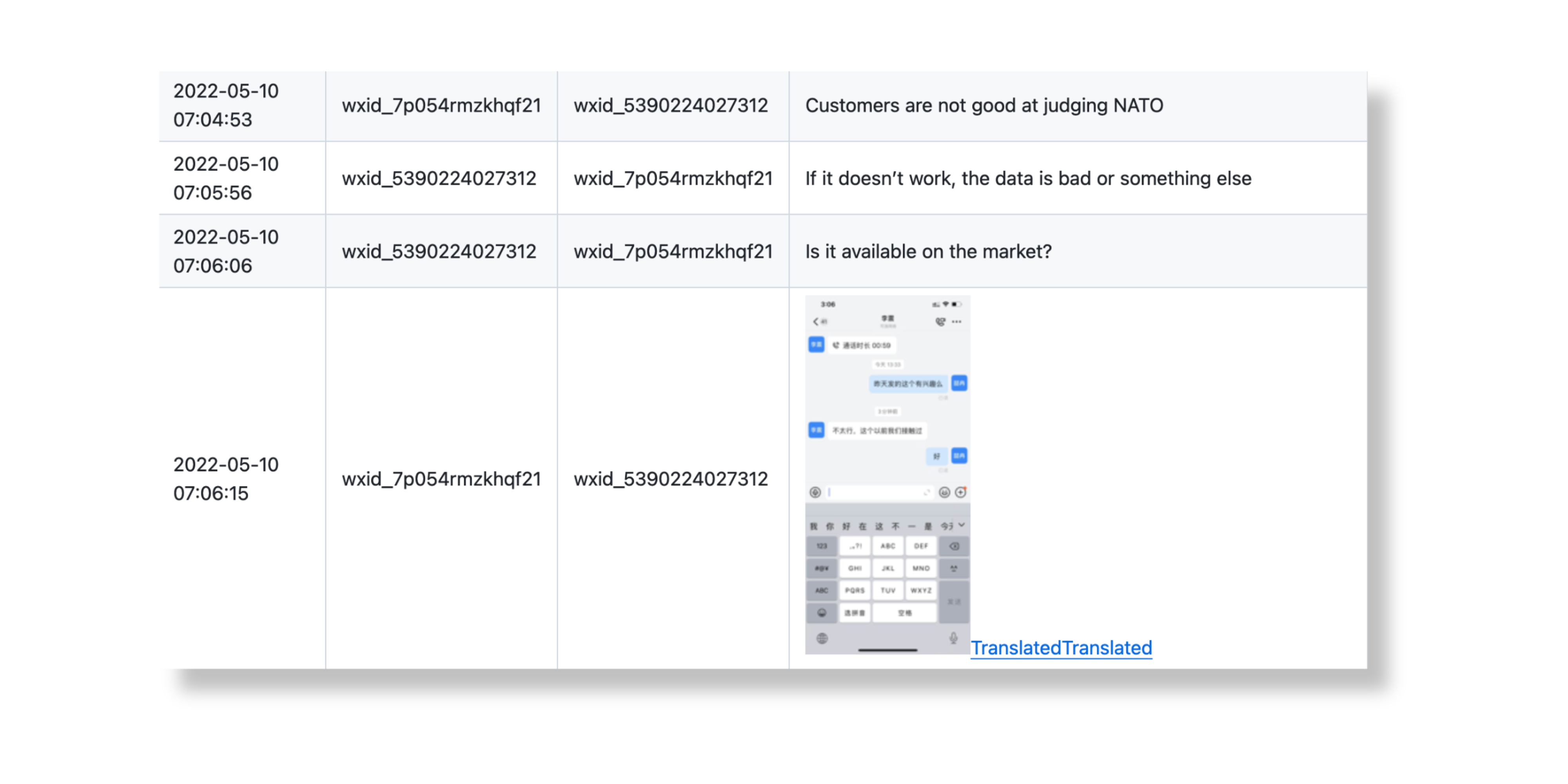

Over the years, iSoon’s targets have included foreign government agencies, diplomatic missions, telecoms companies, newspapers, universities and think tanks in at least 20 foreign territories. The company tends to focus on Asian targets, particularly those in Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, Vietnam, Thailand, and India. However, leaked chat records also contain references to Western nations. In several instances, employees discuss the sale of data from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the UK Foreign Office. It is unclear whether iSoon ever successfully obtained this data.

Figure 1. iSoon employees discuss stolen NATO data

iSoon is also known to have bid for contracts in China's northwestern region of Xinjiang, where Uyghur Muslims have been subject to intense surveillance, mass detentions, and forced sterilizations since about 2014. Uyghurs are a predominantly Turkic-speaking ethnic minority group.[3] Several foreign governments, including the United States, have called China’s actions against Uyghurs a genocide, while the UN human rights office said repression of Uyghurs may constitute crimes against humanity.[4] Based on the available documents, it appears that iSoon’s bid was to assist regional law enforcement and counterterrorism authorities with surveillance of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Who is iSoon?

iSoon operates within a tangled web of Chinese threat actors including state sponsored APTs, contract organizations and hacktivist groups working to advance China’s strategic goals through stealthy cyber operations. These groups frequently intersect and – in some cases – overlap, complicating attribution efforts and making it difficult to gauge the true number of threat actors in operation today. To understand this complicated ecosystem, it is necessary to look at the historical context that propelled China’s hacker-for-hire industry, as well as examining documented links between iSoon and other known threat actors.

Origins of iSoon

Like many Chinese hacking contractors, iSoon has roots in the patriotic hacktivist movement that emerged in the late 1990s. iSoon's CEO, Wu Haibo, is a well-known first-generation hacker and early member of the Green Army, China’s first hacktivist group. Founded in 1997, the Green Army sowed the seeds of hacker culture and paved the way for the nationalist hacker movement in China.[5] After the millennium, a lucrative hacking-for-hire industry sprang up and Wu Haibo put his skills to use in the private sector. He registered iSoon’s domain (isoon[.]net) in 2010 and[6], according to internal documents, set up an “APT network penetration research department” in 2013.[7] In 2020, iSoon was granted a Class II secrecy qualification from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, allowing the company to conduct research and development related to state security. This is the highest secrecy classification that a non-state-owned company can obtain.[8]

A 'lackluster' product offering

In addition to its hacking services, iSoon produces a wide range of software and hardware products. Leaked whitepapers show an impressive array of technologies designed to facilitate state surveillance, data theft and espionage. These include a Twitter (now X) stealer, which enables user tracking and takeover of compromised accounts, Remote Access Trojans (RATs) for Windows x64/x86, and several types of hardware, including advanced spyware for mobile devices.[9] For a more detailed breakdown of iSoon’s product offering, skip to the Annex.

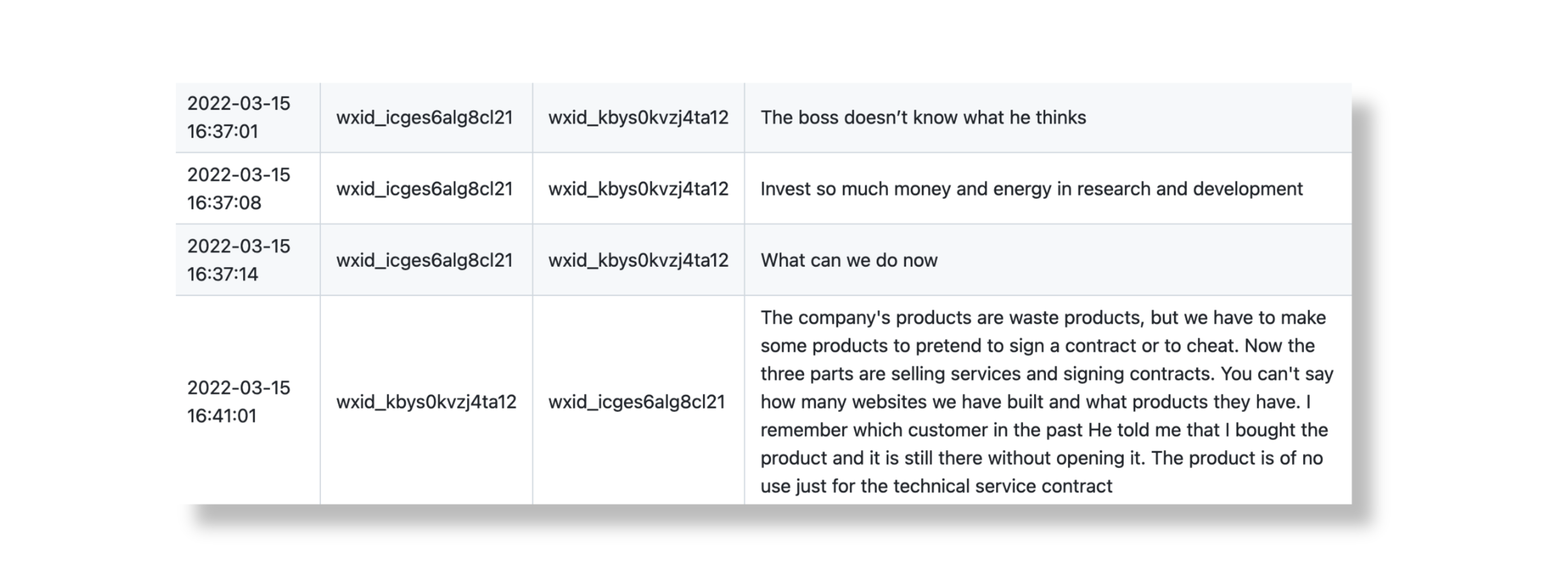

iSoon’s product list certainly appears impressive to outside observers. However, leaked chat records reveal significant dissonance between how the company markets its products and the opinions of employees. In one exchange, an employee remarks that iSoon’s products are “rubbish” and “have no future”. In another, an employee describes them as “waste products” and adds, “but we have to make some products to pretend to sign a contract or to cheat”. In fact, employees make repeated reference to deceiving customers and investors, and using a weak product offering to legitimize iSoon’s hacker-for-hire services. Employees say they focus on selling the company’s services because the products are “lackluster” and “unreliable”. In one conversation, an employee asks, “Are the customers fooling us, or are we fooling the customers?” Their colleague responds by stating that it is “normal” to deceive customers, but it is “not good if the company deceives its employees.”[10]

Figure 2. iSoon employees discuss the company's products

Relationship with APT41 & others

As we have already observed, iSoon operates within a complex landscape of threat actors working to advance China’s strategic goals. It is therefore unsurprising that the leak revealed connections with several known Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups. The company was linked to the APT Poison Carp (also known as Evil Eye, Earth Empusa, EvilBamboo) via an IP address (74.120.172[.]10) that appears to host a phishing website. Another IP address (8.218.67[.]52) was used to connect iSoon with an actor CrowdStrike tracks as Jackpot Panda.[11]

However, the most intriguing relationship highlighted in the leak is the connection between iSoon and APT41 (also known as Double Dragon, Wicked Panda, Bronze Atlas). APT41 is considered one of China’s most sophisticated and persistent threat actors, having been linked to a string of high-profile supply chain attacks and espionage operations since about 2014. Last year, the blog Natto Thoughts reported on a court case between Chengdu 404, which operates as a front company for APT41, and iSoon, indicating some sort of business relationship between the two firms. Chengdu 404 initiated the lawsuit against iSoon over a software development contract dispute and the trial was scheduled to take place on October 17, 2023.[12] Leaked chat records between iSoon executives indicate that iSoon was struggling to pay Chengdu 404 a sum of about €130,000. In another exchange, executives are seen discussing the arrest of APT41 affiliates in Malaysia after US indictments were issued against the group.

Both Chengdu 404 and iSoon maintain offices in Chengdu, Sichuan province, which has been described as a hub for APT activity. It is believed that resources are frequently shared between threat actors here, but hacking outfits also compete for business.[13] Leaked product whitepapers suggest that iSoon had access to the infamous Winnti and ShadowPad malware families, both of which have been used by APT41 and a range of other China-nexus threat actors.

What iSoon reveals about China's hacker for hire industry

The iSoon leak has provided unprecedented insight into the world of China’s state-aligned hacking contractors and challenged many assumptions held by the security community up to this point. Most of us are familiar with the stereotypical image of a hacker, usually presented wearing a dark hoody in front of a glowing screen. However, it appears that in reality China’s hacking contractors are much closer to the average office worker. Chat records show employees exchanging office gossip, complaining about their salaries, lamenting skills shortages in certain departments, and discussing strategies to win new business. Employees express concern about iSoon’s financial standing, mentioning the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and questioning the safety of their roles. In several conversations, employees complain that salaries are too low and say they plan to leave iSoon once the job market improves. Some are in arbitration with the company over unpaid wages.

A Competitive Marketplace

iSoon's financial struggles underscore the fierce competition within China's hacker-for-hire market, where numerous private hacking firms compete for government contracts. And although you would expect these contracts to be quite lucrative, iSoon’s financial records tell a different story. In one instance, iSoon was paid just €50,000 to infiltrate the Vietnamese Ministry of Economy, a sum far lower than you might expect for a government target. In another, employees discuss a NATO project that would have earned the company 70,000 yuan (circa €9,000) per month. One employee remarks that it is “difficult to increase profits for 70,000 or 80,000 yuan” and “100,000 yuan (circa €13,000) is very rare.” Once again, these rates are surprisingly low given the complexity of the task. It appears that China’s large-scale cyber strategy, which incentivizes the creation of private hacking-for hire enterprises, has created a crowded, highly competitive sector that is less lucrative than one might assume.

Proactive vs directed exploitation

Another notable aspect of the leak relates to the dynamic between Chinese hacking contractors and their government clients. Previously, contractors were thought of as receiving specific assignments and direction from customers. However, based on how iSoon operates, it appears that contractors must proactively exploit vulnerabilities and gather data that could provide financial value down the line. In some cases, iSoon employees discuss specific customer requests, while other projects seem more open-ended, and employees are directed to collect any relevant data they can find. This dynamic has likely contributed to the proliferation of mass-exploitation and data harvesting campaigns linked to China in recent years.

China’s outsourcing strategy

The iSoon case sheds light on previously unaddressed aspects of China’s hacking culture and provides valuable insight into the market dynamics shaping the sector. However, to fully understand what is driving the hacker-for-hire industry, we must also consider the broader impacts of China’s outsourcing strategy. Why does China rely so heavily on contractors, and what are the risks associated with doing so?

Military-Civil Fusion

Unlike many other nations that keep cyber warfare efforts centralized within the public sector, China's preference for outsourcing aligns with its goal of integrating industry and the national security apparatus. This has been ongoing since 2017, when Chinese President Xi Jinping enacted the Military-Civil Fusion strategy, which aims to remove barriers between the civilian research and commercial sectors, and the military and defense sectors.[14] The Military-Civil Fusion strategy aims to enlist skilled hackers from prestigious institutions, merge military and civilian cyber ecosystems, and bolster the private tech industry while retaining strong government ties with it. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) also actively recruits civilians with cyber expertise into a militia reserve force to supplement regular military units. It is estimated that more than 10 million people are part of this reserve force.[15] The immense scale of China’s cyber workforce was discussed by FBI Director Christopher Wray last year, when he noted: "If each one of the FBI's cyber agents and intelligence analysts focused on China exclusively, Chinese hackers would still outnumber our cyber personnel by at least 50 to 1." [16]:

Interestingly, iSoon appears to make explicit reference to the PLA reserve force on its website, stating that the company aspires to “become a solid national defense reserve force with a strong sense of political responsibility and a spirit of high responsibility to the Party and the People.”[17] It appears that by outsourcing many of its offensive cyber operations, China has been able to bolster its domestic tech sector and increase civilian cyber capabilities, while still exercising a high degree of control over private sector hackers.

Risk vs Reward

It is also likely that China favors outsourcing due to the plausible deniability it affords when espionage campaigns come to light. By hiding hackers behind front companies and granting these companies legitimacy, the Chinese government guarantees itself a few degrees of separation from anyone who draws international scrutiny. However, this is a double-edged sword, and the benefits must be weighed against the risks associated with outsourcing at scale. This approach introduces additional concerns about information integrity and confidentiality, as exemplified by cases like iSoon and the infamous Edward Snowden/NSA leaks. Although the Chinese government exercises control over both private and public sectors, unauthorized disclosures remain a real risk to the national security apparatus.[18]

Chinese espionage in the Netherlands

The iSoon leak comes just weeks after a Chinese espionage campaign targeting the Dutch armed forces came to light. In February, the Dutch Military Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD) and the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) published a report about a new type of malware found on computers in a military research network. They believe the malware was installed by a state-aligned actor from China, and that the incident is part of a wider trend of Chinese espionage against Western nations, including the Netherlands.[19] We know that the Netherlands is a popular target for state-aligned actors due to its strong economy and reputation for technological innovation. Dutch companies are targeted for trade secrets, R&D, and sensitive data, which can be used to bolster China’s domestic industries and decrease its reliance on Western imports. Ultimately, China seeks to increase its global power through social, economic and military development. Interested in learning more about how China uses cyberspace to advance its goals? Check out our China Threat Profile.

Conclusion

Although iSoon is just one of many hacking contractors operating in China today, this leak has provided rare and useful insights into the competitive hacker-for-hire ecosystem that supports China’s growing cyber capabilities. Leaked documents and employee chat records paint the picture of a cash-strapped company with a frustrated workforce, vying for government contracts in an increasingly crowded marketplace. Hunt & Hackett believes these market dynamics are due to China’s shift towards military-civil fusion in recent years, which has incentivized private contractors to proactively conduct mass exploitation and data harvesting. This case has highlighted both the benefits and risks of China’s outsource-driven cyber strategy and challenged many of the assumptions previously held by the security community.

Nonetheless, further examination is required to assess the relationship between hacking contractors, state sponsored APTs, hacktivist groups, and the role they play in China’s cyber strategy. Although this leak serves as a useful starting point, security researchers have a long way to go before they can untangle the complex web of threat actors operating in China today.

Annex

1. Products

| Product | Features |

|

Twitter (X) Control System |

|

|

WiFi Near Field Attack System |

|

|

Domestic Criminal Investigation System |

|

|

Automated Penetration Testing Platform |

|

|

Email Analysis Intelligence Platform |

|

|

DDoS system |

|

|

Anti-Gambling Platform

|

|

|

Custom Remote Access Trojans (RATs)

|

|

Table 1. A selection of iSoon’s products and associated features

References

- https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240222-massive-leak-shows-chinese-firm-hacked-foreign-govts-activists-analysts

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/02/21/china-hacking-leak-documents-isoon/

- https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

- https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-xinjiang-uyghurs-muslims-repression-genocide-human-rights

- https://medium.com/@theCTIGuy/chinas-green-army-capitalism-defeats-china-s-first-hacking-group-d4c73631d2ca

- https://www.cloudsek.com/blog/chinese-apt-tactics-and-accesses-uncovered-after-analyzing-the-i-soon-repository

- https://github.com/mttaggart/I-S00N/blob/main/0/64bba692-d430-440c-9f1e-2575f45770af_1.png.en.txt

- https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/i-soon-another-company-in-the-apt41

- https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1759326049262019025.html

- https://github.com/mttaggart/I-S00N/blob/main/0/39-en.md

- https://blog.bushidotoken.net/2024/02/lessons-from-isoon-leaks.html

- https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/i-soon-another-company-in-the-apt41

- https://therecord.media/china-commercial-hacking-industry-isoon-leaks

- https://2017-2021.state.gov/military-civil-fusion/

- https://margin.re/content/files/2023/01/China-s-Cyber-Operations-Full-Report.pdf

- https://www.reuters.com/world/fbi-chief-says-china-has-bigger-hacking-program-than-competition-combined-2023-09-18/

- https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/i-soon-another-company-in-the-apt41

- https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3253873/chinas-i-soon-data-leak-exposes-risks-outsourcing-state-spy-operations-hackers-hire

-

https://www.theregister.com/2024/02/06/dutch_defense_china_cyberattack/

- https://www.cloudsek.com/blog/chinese-apt-tactics-and-accesses-uncovered-after-analyzing-the-i-soon-repository

- https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1759326049262019025.html